News

Why Education Sector Philanthropy Must Embrace a Racial Justice Lens

Originally published in Nonprofit Quarterly, February 25, 2021.

A defining theme of 2020 was the nationwide increase in grassroots activism. Across the country, people young and old took to the streets to challenge racial injustice. Whether it was in action on the climate crisis, or in demonstrations in response to fatal police shootings, communities have proven time and again that they care, they are connected, and they are a driving force for change. In the movement to ensure a future and nation that works for all, community organizers have emerged as the real MVPs.

While Black and Brown organizers have modeled extreme heroism and dedication, much of their work has occurred with limited or nonexistent financial support. They are fighting for justice, yet they do so without significant philanthropic investment.

The Schott Foundation for Public Education’s new research with Candid shows that in education, philanthropy drastically underfunds both racial equity and racial justice. In the three-year period from 2017 through 2019, education philanthropy—the second most popular issue for foundations—disbursed $14 billion, but just ten percent of that ($1.4 billion) went to racial equity, and less than one percent ($109 million) went to racial justice. There are 56.6 million K–12 students nationwide, which means the philanthropic investment in racial justice works out to less than $2 per student.

Racial equity and racial justice grants may look similar on their face, but they are different. Racial equity refers to grants designed to close the achievement gap that persists between racial groups. This includes support for programs like racial bias trainings for teachers or mentorship programs for Black and Brown students.

Racial justice refers to addressing the underlying systemic injustices that create these achievement gaps in the first place. Racial justice grants focus explicitly on empowering the people closest to the problem (families and students) as they organize in their communities to change the systems and structures that generate and reinforce racial injustice. Racial justice grantmaking supports building community power, supporting policy change, engaging with policymakers, and building partnerships with advocates to advance racial equity.

From decades of doing this work, we have known anecdotally what the data have now confirmed: Philanthropy is failing to combat the systemic harms that young people of color experience. Funding data from 2011 to 2018 indicate that overall philanthropic giving increased dramatically, growing 48 percent. At the same time, the proportion of philanthropic dollars for K-12 education shrank slightly, by seven percent. Funding for racial equity and justice, however, fell by 36 percent in the same interval.

Philanthropy, when it does engage in racial justice grantmaking, tends to fund in the context of community organizing or community development, but it falls short in public education. The fight for justice doesn’t stop when a child enters a school building or logs on to remote online learning. Achieving racial justice in society as a whole requires using a racial justice lens in education grantmaking.

The challenges are widespread: In Colorado Springs, Colorado, police were called to a child’s home after his teacher reported that he was playing with a toy gun. In Kissimmee, Florida, a Black teen girl was knocked unconscious after she was body-slammed by a school resource officer. Funding must be comprehensive; investing in short-term “silver-bullet” solutions won’t address systemic and long-term needs. Most importantly, community organizers have shown us they can achieve transformational systems change. Now we must give them the resources to do so.

We have seen what happens when community organizers get support and resources. After a yearlong campaign by Black and Brown youth and their families supported by grassroots organizers, the Los Angeles Unified School District agreed to restructure its relationship with police—limiting police presence in schools, banning the use of pepper spray on students, and diverting funds from the department to improve Black students’ education outcomes. Students had long pointed out that police disproportionately targeted Black and Latinx students. It’s one thing to dismantle or restructure relationships, but organizers have to continue to fight for the school board to reinvest those resources to fund counselors, social workers, and other key supports. They need philanthropic support to do so.

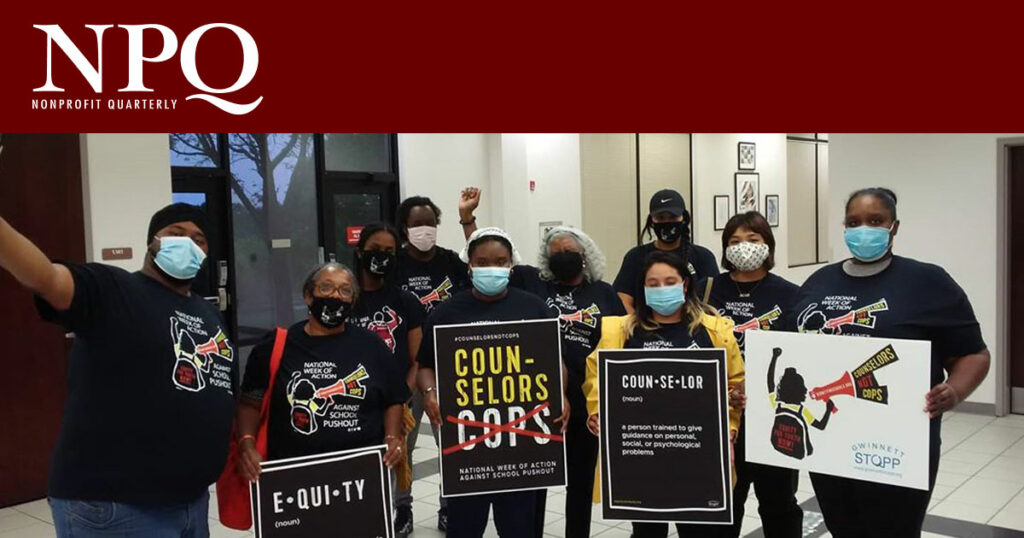

Activists in other parts of the country have also successfully organized to limit police involvement and presence in schools, as well as advocating for student supports and equity. The Minneapolis Board of Education voted to sever its relationship with the Minneapolis Police Department, which had been the recipient of more than $1 million in education funds to put its officers in schools. The danger of police officers in schools—and their contribution to the school-to-prison pipeline that threatens so many children of color—is well documented. Their removal has been a central demand of education justice organizations, including our foundation, members of the Dignity in Schools Campaign, and the Alliance for Educational Justice.

In Arkansas, students and families organized to help restore the Little Rock School District (LRSD) to local community control. Grassroots Arkansas, which our foundation has supported, was a key member of the coalition to fight for local oversight and accountability of the district’s budget and administration. That the home of the Little Rock Nine had been deprived of democratic control over their public schools was a tragedy, one that has thankfully been reversed. LRSD voters have now elected a nine-member school board for the first time since 2014.

There is no question that community organizers and organizations are making a difference. Imagine how much more they could do with funding dedicated to achieving racial justice in education.

Our public education system shapes both our leaders and our future. This means supporting communities to have the power to envision and demand the excellent public education systems that they want: systems that culturally affirm them, leverage their brilliance, challenge their thinking, and prepare them to live in and lead in the future. Investing in racial justice in our education system is one key strategy to get to a more just world. We must bend the arc of funding toward justice.

Leah Austin, Ed.D., is director of the National Opportunity to Learn Network at the Schott Foundation and an Atlanta-based educator, advocate, and futurist.

Edgar Villanueva is senior vice president of programs and advocacy at the Schott Foundation, and author of Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance. Villanueva is proud to be an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, as well as a Southerner—lineages from which he inherited his love of storytelling and strong devotion to community.