News

Vox Interviews Edgar Villanueva on the Racial Philanthropy Gap

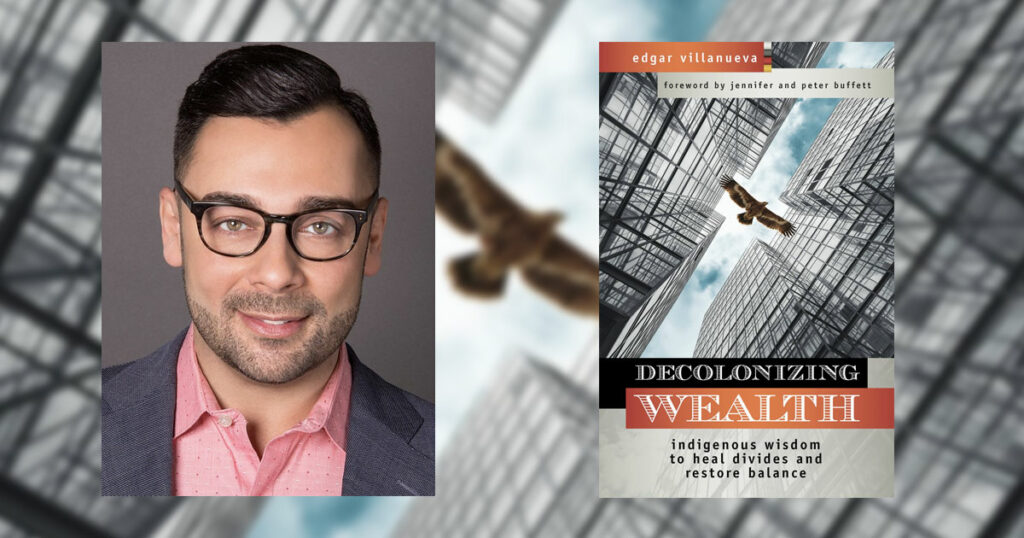

In a recent interview by Dylan Matthews at Vox, Schott Vice President of Programs and Advocacy Edgar Villanueva described how the racial wealth gap has translated to a similar gap in philanthropic giving: a bias in how that wealth is dispersed, which keeps control away from people of color, and minimizes donations to groups run by people of color for the benefit of communities of color.

Dylan Matthews

Walk me through some of the racial equity problems facing philanthropy: What are some of the representational and grant-making gaps you’ve discovered?

Edgar Villanueva

Many families and many institutions that have amassed wealth have done so on the backs of people of color and indigenous people. One example I often share is my first job in philanthropy was in North Carolina, and it was all tobacco money. My office was on a plantation.

The R.J. Reynolds family had amassed all this wealth through the tobacco industry. Clearly, slave labor was a major part of that and helped to build this family’s fortune. There are multiple Reynolds foundations that now exist. I think that [money] should be given in a way that sort of centers and prioritizes giving in communities of color that helped amass that wealth.

The latest research that came out from the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equality shows that only about 8-9 percent of grant-making from foundations goes into communities of color [in the US].

And so, when you take the historical account as to how indigenous communities and how people of color have contributed to building wealth in this country, and the trauma that exists because of how wealth was accumulated, I think that it’s an easy case to make that philanthropic capital should at least be more inclusive of those communities.

I also think [part of the] race conversation [is] around who actually gets to control, allocate, manage, and spend that money. We have a major diversity issue. 92 percent of CEOs of foundations, 89 percent of executives on foundation boards, 81 percent of management for financial services and 86 percent of venture capital investors are white. We often give to people in our network, and to people that we know and look like us. And so because of that major diversity issue in philanthropy, resources are not going to communities of color.

Dylan Matthews

One of the more disturbing dynamics you write about is this phenomenon where organizations representing communities of color come in and are forced to beg philanthropic grant makers for resources that you argue were earned through processes of exploitation in the first place. Could you talk a bit about how that dynamic influences philanthropy?

Edgar Villanueva

This is where I connect some of the dynamics in philanthropy back to dynamics of colonization. It’s so important for us all to understand the history of this country and how wealth has been accumulated.

I don’t think anyone comes to work into a foundation with any intention to be racist or hurt people or harmed community, but it’s in that lack of understanding of how we’re doing our business that perpetuates the divisions between the haves and the have nots.

One easy example of that is when you look at the application process for many foundations and the bar that we hold organizations to, and who we esteem to be experts in the work that we’re funding. There are no types of adjustments made for folks who are coming from communities of color, or from backgrounds that have been marginalized.

I’ve been in many, many conversations where we’ve been discussing who gets the money, right? We’re looking at the slate of applications and folks will just say things like, “Well, this particular organization, they have more resources, they’re more financially viable, so this is a safer investment.”

For the past 70 years, foundations have [already] been funding that type of nonprofit. So of course they have more resources in the bank, and a bigger staff, and the development director who can write a very strong grant proposal. It’s very simple things like that that I’m bringing to the attention of grant makers.

If we as a sector are really sincere about equity, and not just diversity but equity, that means that we have to overcompensate and give a boost to those organizations that have not been receiving resources for the past 70 years. We’ve got to make up for lost time.