Blog

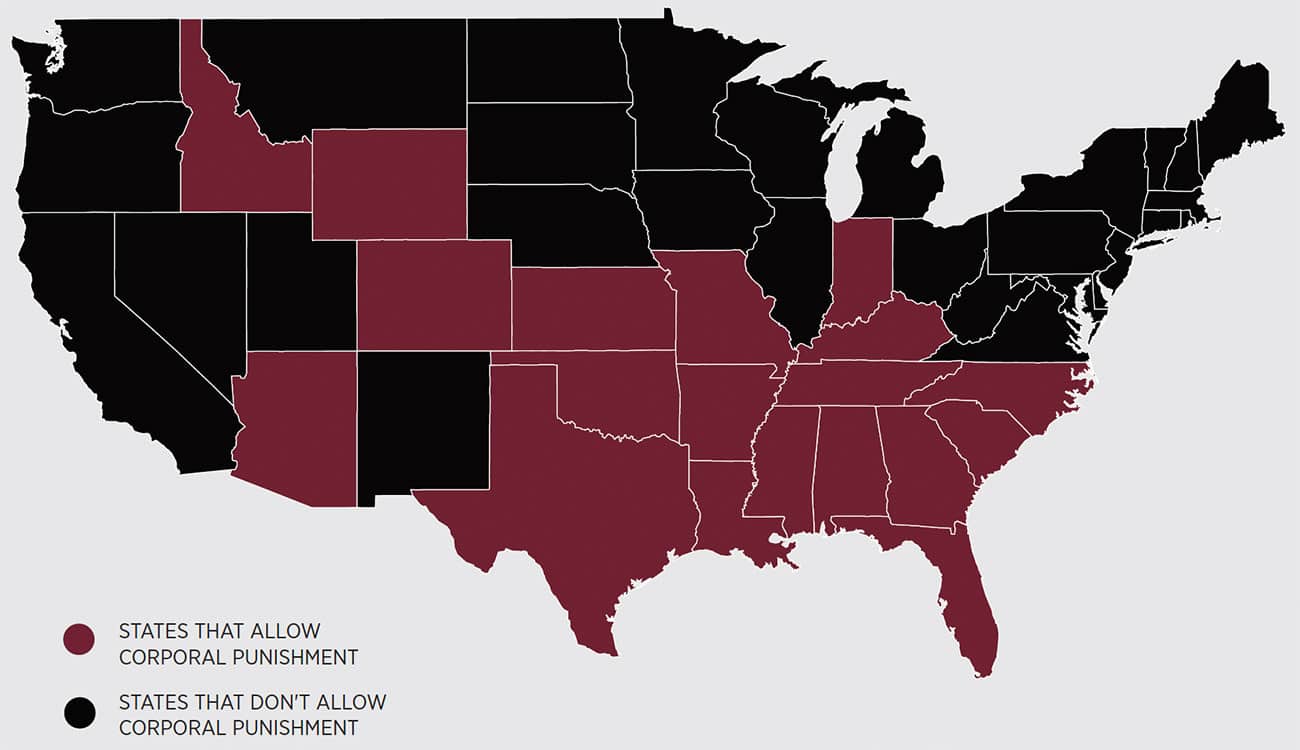

Unacceptable: Nineteen States Still Allow Corporal Punishment

The advancement of school discipline reform has been a bright spot among what often feels like a sea of bad news in education. Coalitions like the Dignity in Schools Campaign and national groups like the Advancement Project and NAACP have long highlighted the unjust, inequitable and ineffective school discipline policies that far too many children attend school under. Studies consistently show the school-to-prison pipeline is built on a bedrock of white supremacist, patriarchal, heteronormative and ableist biases. Fortunately, innovative cross-sector organizing uniting young people, parents and educators have been able to push positive reform policies in states and districts across the country—first by curbing harmful punishments like suspensions and expulsions, and then by introducing positive policies to replace them, like restorative practices and accountability processes that center healing instead of punishment.

However, a new report shows just how uneven these reforms have been implemented, and how desperately far many states and districts need to go.

The Striking Outlier, co-authored by the Southern Poverty Law Center and the UCLA Center for Civil Rights Remedies, details how nineteen states still have corporal punishment as an acceptable disciplinary practice in their public schools. For those nineteen states,

educators in public schools are allowed to do what employees in many prisons, juvenile detention facilities, daycare and early learning centers can’t do by law—strike another person as punishment.

Nor is this unconscionable practice a dead letter, a mere relic from an older time and no longer practiced. So many students are being struck each school year that the total adds up to 600 students—from preschool to high school—suffering corporal punishment each day.

Corporal punishment can be imposed on many students for frankly minor infractions of school code, including:

- Untucked shirts

- Tardiness

- Going to the bathroom without permission

- Walking on the wrong side of the hallway

- Running in the hallway

- Failing to turn in homework

- Using a mobile phone

- Sleeping in class

- Talking back

- Sitting in an unassigned seat

- Failing a test

- Talking out of turn

- Stepping on another student’s feet

- Laughing at an inappropriate time

- Behavior that may arise from behavioral and

other disabilities

Especially with the latitude given staff and administrators at these schools, we see corporal punishment coming down disproportionately harder on children of color and those with disabilities. For example, staff in Lake County Schools, Tennessee, “struck students with disabilities at a rate of 60.7 percent in 2013–14, compared to 15 percent of students without disabilities.” The report found that among boys, Black students have the highest corporal punishment rates, 14 percent, compared to their white counterparts at 7.5 percent. The racial gap among girls is even starker, with Black girls suffering a rate of 5.2 percent compared to 1.7 percent for white girls.

And in case anyone in 2019 needed convincing, Striking Outlier reminds readers of the mountain of evidence showing the detrimental effects of corporal punishment and the paucity of any that suggest positive outcomes:

There’s no shortage of literature describing the negative outcomes of corporal punishment. A 2016 review of more than 250 studies found the practice linked to a range of negative consequences, from physical and emotional harm to poor academic performance. It did not find evidence of any positive outcomes. What’s more, the practice fails to teach students social, emotional and behavioral skills.