Blog

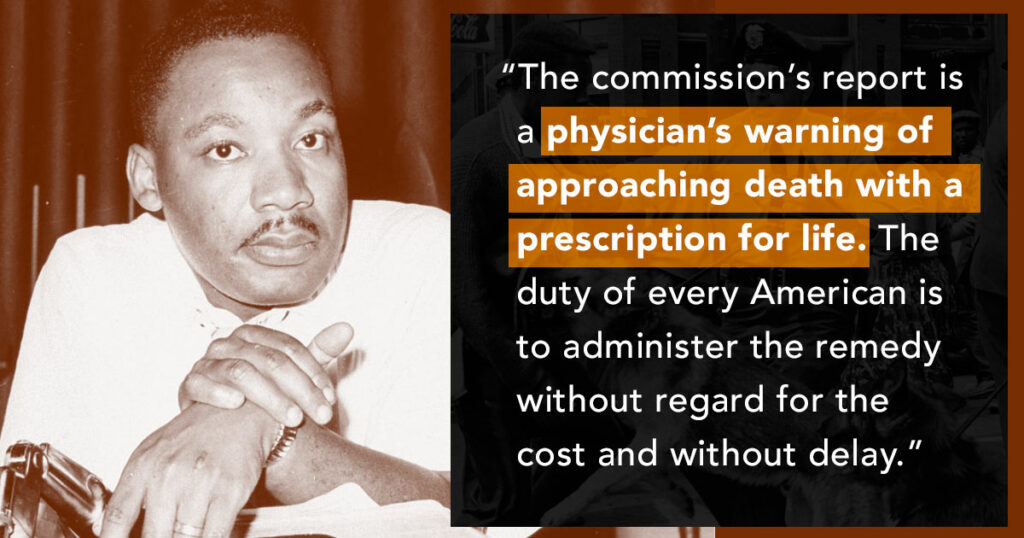

The Report that MLK Called a “Prescription for Life”

In March, 1968, while much of the national media’s attention was fixed on the presidential election campaign, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were organizing a campaign of a different sort: the Poor People’s Campaign.

In this politically charged environment, the Kerner Commission Report exploded onto the scene. In response to Black rebellions in cities across the country, the Johnson Administration had assembled The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, chaired by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner. The report’s findings, surprising even Johnson himself, took a detailed look at the root causes of unrest in America and proposed solutions as bold as the ills confronting the nation. As a Brookings retrospective detailed:

Their report, issued in March 1968, argued that the riots were caused in large part by poor neighborhood conditions and limited labor market options facing black Americans as a consequence of racism and rampant discrimination in housing and labor markets.

These factors underlay the development and maintenance of the northern black “ghettos”, where residents endured extreme segregation, limited housing choices, concentrated poverty, and poor schools. The Kerner Commission found the civil rights acts and Great Society programs of the 1960s didn’t go far enough. The report argued for massive government investments in public education, housing, and jobs, alongside the ending of racist police violence and active anti-discrimination campaigns.

King saw the potential of the commission’s report, and a few days after its release, gave its findings and recommendations a glowing endorsement. He described it as “a physician’s warning of approaching death with a prescription for life.” But he knew that absent a grassroots movement, the report would simply gather dust on the shelf:

Eloquence and analysis by themselves do not bring change. Bitter experience has shown that our government does not act until it is confronted directly and militantly. King would be assassinated in Memphis a month after writing those words, and like so much that emerged in the 1960s, the promise held within the Kerner report and the Poor People’s Campaign remains unfulfilled. Justice was delayed.