Blog

The Fight for Public Education in Puerto Rico: 3 Lessons for the Field & Philanthropy

Like flowers blossoming after a storm, deep and widespread social movements in Puerto Rico have emerged to confront the brutal austerity regime imposed by Wall Street and Washington, DC and enforced by the island’s own political and economic elites. The summer of 2019 saw over a million Puerto Ricans take to the streets and go on strike against Governor Ricardo Rosselló and all that he represented, culminating in his resignation on August 2nd.

But leading up to the fight against Rosselló were massive waves of education organizing and protest involving educators, students and parents against back-room deals that would have gutted educator benefits and privatization plans to shutter hundreds of public schools all across the island.

Yesterday we convened organizers from across the country to highlight the popular struggles in Puerto Rico against austerity, privatization, and the larger neocolonial project the island has been subjected to. Members of Schott grantee partner Journey for Justice Alliance have visited the island to support and learn from the struggles there, including co-organizing a conference this past summer.

Our presenters included:

- Zakiyah Ansari, Advocacy Director & New York City Director, Alliance for Quality Education

- Jitu Brown, National Organizer, Journey for Justice Alliance

- Jorge Díaz Ortiz, Executive & Artistic Director, Agitarte

- Mercedes Martinez, President, Federación de Maestros de Puerto Rico (Teachers Federation of Puerto Rico)

- Marianna Islam (moderator), Director of Programs and Advocacy, Schott Foundation for Public Education

View the entire webinar here:

Here are three key takeaways from the webinar.

1. Struggles for education justice are linked — advocates should be too.

Schott’s Opportunity to Learn Network is a growing network of interconnected local, state and national racial justice leaders in the education justice movement. It includes members from the Journey for Justice Alliance who are building national and transnational solidarity toward solutions.

As Jitu Brown put it, “The fight against school privatization is not new in the United States and it’s not new on the island. Brave parents and community members and educators have been fighting school privatization in Puerto Rico.”

The playbook of privatization — mass school closures, attacks on employee pensions, and the imposition of charter schools — is the same one used both in Puerto Rico and on the mainland. “After hurricane Maria, there’s been an effort to do similar to what’s happened in New Orleans: to take advantage of human disaster… to privatize,” Brown said. Zakiyah Ansari described the post-disaster exploitation as “vultures that come in and try to tear up our communities, it’s something that’s very relatable” to cities across the country.

Members of Journey for Justice Alliance and organizers in Puerto Rico found cooperation natural. As Brown described it, “When we started talking to each other we realized we were going through the same thing. Often, policy initiatives that may have started somewhere else are just repackaged and sent somewhere else. And also in what our children need we were on the same page. We knew we needed community schools, we knew we needed to end zero tolerance policies. Us building unity wasn’t hard.”

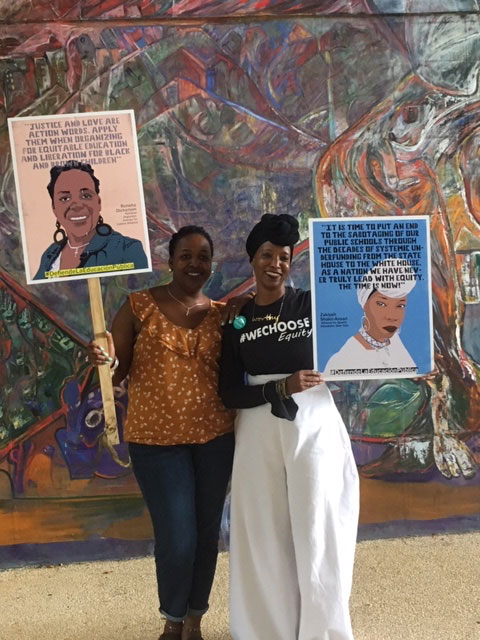

Organizers came together, lifting up and sharing each others’ stories and experiences. “The stories we share and offer as a way to unify but also to fight back,” Ansari said. “We can learn from each other.” One of the things that Ansari found powerful at their conference “was the centering of women of color: how our power, that of Black and brown women, is so centered in what we do.”

Zakiyah Ansari (right)

Mercedes Martinez (left)

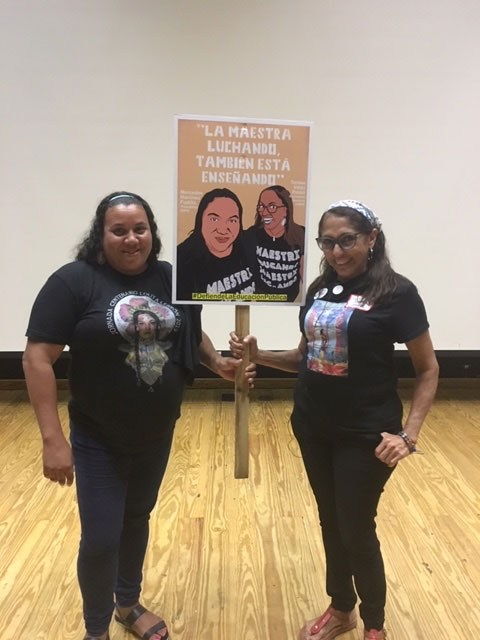

Agitarte’s Executive & Artistic Director Jorge Díaz Ortiz detailed the ways that popular education and art was integrated into the struggle for education justice. “When we’re talking about cultural organizing we’re talking about organizing, just with culture as an entry point.”

Click here to see more of AgitArte’s work

2. Attacks on public goods and attacks on democracy go hand-in-hand.

The abolition of democracy in public education, through attacks like state takeovers, mayoral control, and other emergency measures, is often the first stepping stone in bypassing the community and forcing drastic policy changes upon them. From Chicago to New Orleans to Puerto Rico, it’s a tried and true tactic.

Díaz said that while attacks on the public sector have been ongoing for many years, “Really the big thrust to shut down schools starts with the imposition of the Fiscal Control Board, which was a measure that the White House under President Obama did with bipartisan support. It established a dictatorial board that is over the Puerto Rican government.”

This is an important lesson for communities so they can see what’s coming: if elites go after democratic institutions, privatizations and sell-offs will not be far behind. But it also means that the positive projects of public reinvestment and re-democratization must go together as well: if we win the former without winning the latter, it’s easy for those victories to be rolled back.

Resisting these attacks takes the grassroots coordination and integration of people across varied groups and locales, including students, parents, educators, and community members who are willing to invest their resources and take the needed risks to pressure policymakers and economic elites.

As Federación de Maestros de Puerto Rico (FMPR) President Mercedes Martinez wrote in Labor Notes in August,

This has been a glorious summer, where hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans participated in the biggest general strike ever on the island. The strikes and demonstrations that brought down the Roselló regime were largely spontaneous and broadly democratic, but the seeds of the insurrection were planted by decades of struggle.

These struggles have been led by feminists who fought against gender violence and homophobia, muckraking journalists who uncovered the depths of government corruption, activists organizing for the debt to be dropped, community members building autonomous centers of self-organization, environmentalists who stopped a pipeline, students who went on strike to keep their universities public, artists who preserved and created culture, and unionists who refused to compromise away working people’s futures.

No one party, organization, or union called for the strike and demonstrations. Many groups contributed to their outbreak and political character.

If we can learn something from this victorious moment, it is that the road ahead lies in fighting back for the future and refusing to compromise.

3. People-powered organizing can halt the advance of privatization and build momentum toward positive reforms.

Many of the proposed school closures and characterizations have been halted or reversed due to direct action taken by communities. One closed school on the island was occupied by students, parents, and educators for 165 days, at which point they succeeded in having the school re-opened.

FMPR is a good example of a social movement union: an organization that’s based in communities and works alongside other organizing groups. FMPR is one of the key groups that spearheaded the recent protests against Governor Rosselló that have expanded into a larger, more comprehensive struggle. “FMPR as a union has deep roots in many communities,” Brown said, “so there’s a strong relationship with parents, with students, with other organizers and activists.”

Despite a law imposed two years ago that would have allowed the conversion of 10% of the island’s schools to charters, “only two schools out of 856 have been privatized,” FMPR President Mercedes Martinez said. “And that is because of the battles that teachers, students and parents have given in defense of public education.”

Grassroots organizations like Journey for Justice have also brought tried-and-tested solutions to the crisis: ones that can work across many contexts, like sustainable community schools and the replacement of harmful and racially-biased school discipline policies with restorative justice; as well as ones that are specific to Puerto Rico, like the abolition of PROMESA (the island’s unaccountable fiscal control board) and the reinvestment of public funds into pensions, schools, and public services.

Jitu Brown emphasized that it is within struggles against the worst that we can begin to imagine the best. “It provides a moment to dream about what education might look like on the island.”

What role can philanthropy play?

Zakiyah Ansari emphasized how important it is that funders help create these kinds of learning and healing spaces where participants can do the crucial work necessary for genuine and lasting movement-building. Philanthropy should be listening to people and providing what they tell us they need and when they need it, not simply providing what we think they need, on our own timeline.

Schott was able to provide rapid response support for this important organizing and convening because we had already built trust with our partners and learned from them where opportunities exist for the greatest impact. Schott is already working with other funders to offer this kind of support to our grantees, and we are looking to expand: we encourage other funders to collaborate with us in supporting this important work.