Schott Summer School: Six youth organizing lessons from across the country

As millions of young people are returning to school for the fall, youth organizing is ramping up. We talked with folks at three of our grantee partners to learn practical lessons from the latest generation of youth organizers as they build movements for justice both inside and outside of school.

Like what you’re reading? Don’t miss our next issue. Sign up for our monthly newsletter:

California Native Vote Project (CNVP), formed in 2016, is a statewide organization that aims to achieve equity and justice for Native American children, families and communities by increasing Native civic participation and power. Native youth have been pivotal to its activities from the outset, both as a constituency to be mobilized and as organizers in their own right. Its annual Indigenous Youth Organizing Academy brings together young activists from across the state to learn, strategize, and build community.

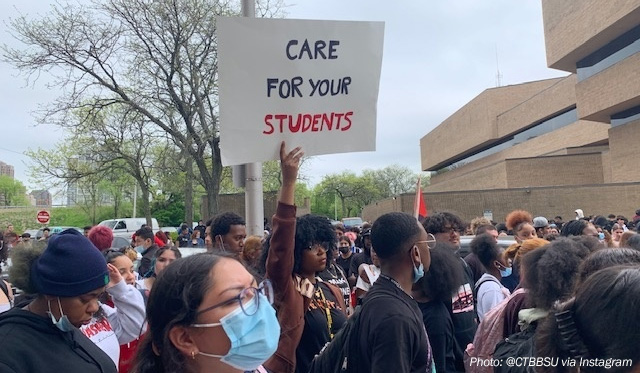

Connecticut Black & Brown Student Union (CTBBSU) emerged as a coalition of grassroots youth groups in 2018 to build capacity for statewide organizing, train youth organizers, and build power around youth priorities in Connecticut. The organization and its member groups celebrated a massive victory in June with the passing of an extensive public school reform bill that adds new regulations and transparency on school resource officers (SROs), requires restorative practices be implemented in schools, and provides funding for more wraparound supports for students.

Georgia Youth Justice Coalition (GYJC) first formed in January 2021 as a grassroots collective of Black, brown, LGBTQ+, working class, and allied students advocating for youth power and justice in Georgia. The past two years have seen immense growth in their size and reach, organizing both at high school and college levels in 19 counties and across many issue areas, building a strong base, educating members and the public, and advocating for change at all levels of government.

1. Meet young organizers’ needs — including paying them.

The picture often portrayed in mass media of the tireless young volunteer campaigning to save the world has always been a misleading one. It’s especially misleading now, as young people must juggle their studies, a job, family responsibilities, and pay bills amid a worsening housing crisis and precarious employment.

CNVP’s Calvin Hedrick, Community Organizer for Northern California, described the importance of supporting youth participants even when the events are virtual, like when the first Indigenous Youth Organizing Academy, in 2020, had to be moved online due to the pandemic. “Instead of spending money on food for youth there, we sent out a gift card so that everybody can be eating lunch while they’re on.”

CNVP’s Calvin Hedrick, Community Organizer for Northern California, described the importance of supporting youth participants even when the events are virtual, like when the first Indigenous Youth Organizing Academy, in 2020, had to be moved online due to the pandemic. “Instead of spending money on food for youth there, we sent out a gift card so that everybody can be eating lunch while they’re on.”

Paying youth organizers for their invaluable work is not only a matter of fairness — if they’re performing labor for you, you should pay them — but also a strategic investment in the future of social change. Recognizing and compensating the efforts of young organizers acknowledges their commitment, time, and expertise, validating their contributions as essential components of any movement.

Yana Batra, GYJC’s Campus Mobilization Director said, “we structure our pay in ways that make the work accessible to folks who can only dedicate five hours a week and can’t take on those part-time or full-time positions. Proving that paying young people actually builds investment in the work has been something that we’ve been trying to do for the past couple of years and has really paid off.”

“We need to provide food, we need to provide transportation, we need to provide a stipend right for their time,” said CTBBSU Executive Director Sarana Nia. “That’s kind of non-negotiable when you’re dealing with young people.”

When youth organizers are compensated in ways big and small, it demonstrates that their dedication is valued and that their work holds real worth. Financial support enables them to fully engage without sacrificing their personal responsibilities or economic well-being.

“I’ve started using this quote that I heard a while ago by an by an elderly Black organizer,” Hedrick says. “He said, ‘How are we spending the people’s money today?’ And that just really makes me feel like, what are we doing to ensure that the people that we work with are getting the very most that they can?”

2. Engage young people in planning and governance at the earliest stages.

Meaningful engagement not only empowers young leaders to shape the direction of the organization but also fosters a sense of ownership and investment in the outcomes. When youth have a seat — or ideally, several — at the table, it reinforces the principle that their voices are valuable and deserving of attention and puts rhetoric of youth power into practice.

It is difficult for an organization to include youth voice and participation in a meaningful way if it’s not in its DNA from day one. “I’ve seen a lot of different models over the years,” Nia said. “And I think one thing I can certainly say is that an organization that was not founded to center youth will not center youth.”

It is difficult for an organization to include youth voice and participation in a meaningful way if it’s not in its DNA from day one. “I’ve seen a lot of different models over the years,” Nia said. “And I think one thing I can certainly say is that an organization that was not founded to center youth will not center youth.”

For CNVP, the planning starts with their paid youth organizing staff, but doesn’t end there. “We have two staff who are 22,” Hedrick said. “We have youth who are 18, who are 15, and who are 13.” Having those conversations led by younger people is also key on a practical level of relatability. “You’ve got to have young people on there, so that a 13-year-old kid can see another 13-year-old kid who’s speaking and think, ‘it’s about me too. I see myself in that person, too.’”

Keeping young people at the heart of decision-making also makes these organizations more nimble and responsive to both long- and short-term priorities. At GYJC, the program leads are all students and they make the bulk of programmatic decisions. CNVP members are changing local school names, updating curriculum, and as an organization were able to quickly and successfully mobilize community members to protest when a teacher had pulled on a Native student’s traditional braid and threatened to cut it off. In the wake of CTBBSU’s legislative victory early this year, young people are driving the next priorities, including diversifying the educator workforce.

3. Have a clear ladder of engagement for volunteers, and a career path for seasoned organizers.

A well-defined engagement ladder guides newcomers step by step, from initial interest to becoming seasoned advocates. For GYJC, it will often start with a conversation with an organizer who’s tabling for the group. “Right now, for both our high schoolers and our college students, we are running what we’re calling the Young People’s Platform,” Batra said. “We’re trying to solicit a ton of information from students across the state and compile them all into a platform of issues.” That first conversation can turn into a one-on-one meeting later, and then joining GYJC’s Student Power Hub, which provides regular action opportunities — like calling electeds, or providing testimony to legislators — as well as providing fun events like game nights to build community. Just last month, the group held its first Education Justice University Summit, an event for Georgians aged 14-22 that offered free food, speakers, workshops, and ways to get involved (and reimbursement for attendee travel expenses).

A well-defined engagement ladder guides newcomers step by step, from initial interest to becoming seasoned advocates. For GYJC, it will often start with a conversation with an organizer who’s tabling for the group. “Right now, for both our high schoolers and our college students, we are running what we’re calling the Young People’s Platform,” Batra said. “We’re trying to solicit a ton of information from students across the state and compile them all into a platform of issues.” That first conversation can turn into a one-on-one meeting later, and then joining GYJC’s Student Power Hub, which provides regular action opportunities — like calling electeds, or providing testimony to legislators — as well as providing fun events like game nights to build community. Just last month, the group held its first Education Justice University Summit, an event for Georgians aged 14-22 that offered free food, speakers, workshops, and ways to get involved (and reimbursement for attendee travel expenses).

Hedrick emphasized the importance of training young people from the start. “This year, my students really tried to hammer our organizing model, to get involved in a campaign, to develop those relationships,” he said, “and to understand what it means to have a clear vision that everybody’s going to agree on and develop a strategy.” He also highlighted the importance of hands-on trainings like event planning and public speaking.

For organizers who have built up years of experience, is there a logical next step for them once they’ve “aged out?” For Nia at CTBBSU, this is a crucial question, one tied up with organizational resiliency and financial stability. “We can certainly develop leadership and develop capacity. But are we developing organizations that can hold employment? To hold people in the work?”

For GYJC, as it’s still so new there hasn’t been a generation of participants who have stepped off yet, but many of those who have are doing organizing work in groups across the country. “We focus really hard on keeping our alumni tied in with GYJC,” Batra said, “and able to offer advisement and systems of support for our younger staff.”

4. Build your base beyond school walls.

A high school can be a difficult place to organize for students who attend there, and even more so when it involves young people at other schools as well.

The pandemic drop in undergraduate enrollment, combined with a stubborn 40% college dropout rate, also means that there are many young people who have left school entirely and are working part- or full-time. School-centered outreach strategies can miss that crucial population.

“We try and find the spaces and communities where high schoolers are together and building community for themselves,” Batra said. “That might look like a square, or a boba shop. It’s a variety of different places. Since the pandemic more people tend to go to parks now, or often they meet at someone’s home.” The fragmenting of common meeting and hangout spots also requires new emphasis on social media for local outreach, even on the comparatively more open and spacious grounds of universities: where once fliers in coffee shops and on campus might be enough, now youth organizers are doubling down on reaching people through their phones.

Nia identified an additional concern when it comes to the traditional route of using the school as your meeting and organizing hub, especially for groups with radical aims. “For me, if you want to do something radical, you don’t try to do it inside of schools,” they said. “My suggestion would be to find a small organization and work with other small youth groups in your city, outside of a school building, and figure out what you want to do.”

5. There’s more overlap between high school and college students than you think.

Despite changing college enrollment patterns, high school and college years for young people are usually eight formative years in a row. While their institutions change, there is still significant overlap in material conditions, interests, and priorities.

GJYC has shown what’s possible when youth power is built across those institutional dividing lines. One example Batra gave was the group’s participation in the Stop Cop City campaign, which recently won a spot on the ballot as a referendum. Their members have knocked on doors every weekend, collecting signatures from Atlantans to halt the construction of the facility. Batra explained how that campaign unites high school and college students: “The school-to-prison pipeline is alive and well, and our students, especially in Atlanta public schools, are facing the possibility of leaving their schools in handcuffs, when they should instead be receiving things like mental health counseling.” Cop City would train Atlanta public school’s SROs, expanding a militarized police force that both high school and college students will have to face. And for climate-minded youth of all ages, the fact that the facility would tear down a massive area of forest around the city has proven a galvanizing issue for students across the state and country.

Batra herself is evidence of the power of organizing across secondary and tertiary education: she joined GJYC as a junior in high school, and now, as a college sophomore she is Campus Mobilization Director.

6. When including youth in decisions, don’t tokenize, don’t romanticize. Do respect.

Tokenization of young people in movements has long been recognized as a problem, but that doesn’t mean it’s close to being resolved. Tokenization can be recruiting some young faces for a photo op or press conference or adding youth mobilization as a last-minute add-on to an existing plan. It teaches young people that they are objects, not subjects, of politics, and that they and their priorities and gifts are disposable, not valuable. doesn’t just happen inside organization, but in coalition spaces as well. “It’s impossible to get young people in a space if we’re not able to shape what the space looks like and make it accessible,” Batra said, “It’s not fair for you to tell us you’re having an event at 10am on a weekday, two weeks out, and ask us if we can recruit 20 young people to be there.”

Romanticizing youth participation happens at the opposite end of the spectrum as tokenizing. Sometimes adult allies can abrogate their duties and responsibilities in the name of letting young people decide. The danger, as Nia puts it, is that “we just over-romanticize the abilities and skill level of young people, so that we can say ‘young people are doing it,’ but we’re actually just watching poor decisions be made, and then saying, ‘we’re letting the young people lead.’”

“We do need adult experience in the room,” Batra said. “I think for adult mentors, it’s about building infrastructure, meeting regularly with students, and making sure that students are dictating how programming forms, while at the same time holding those guardrails for folks. Adult mentors should act as a guardrail: let your students make mistakes, mistakes are good, but don’t let them do something devastating to the organization or something that’s going to waste a ton of money.”

Further Learning

Organizing & Narrative Toolkit — download and use HEAL Together’s latest organizing guide, an extensive toolkit designed to help communities push back against the far right and build power for equity and justice. Along with the Schott Foundation, Georgia Youth Justice Coalition is a HEAL Together partner organization.

Frequently Asked Questions — The Funders’ Collaborative on Youth Organizing has assembled a useful FAQ for donors and foundations considering adding youth organizing to their funding work.