Blog

New Report: School Resource Officers, Girls of Color, and the School-to-Prison Pipeline

Schools across the country increasingly rely on school-based police officers. Today there are an estimated 30,000 officers now in schools, up from roughly 100 in the 1970s. Although the stated purpose of these officers is to maintain a sense of safety, a very troubling consequence is greater arrest rates and referrals for minor disruptive behaviors — with especially harsh results for girls of color.

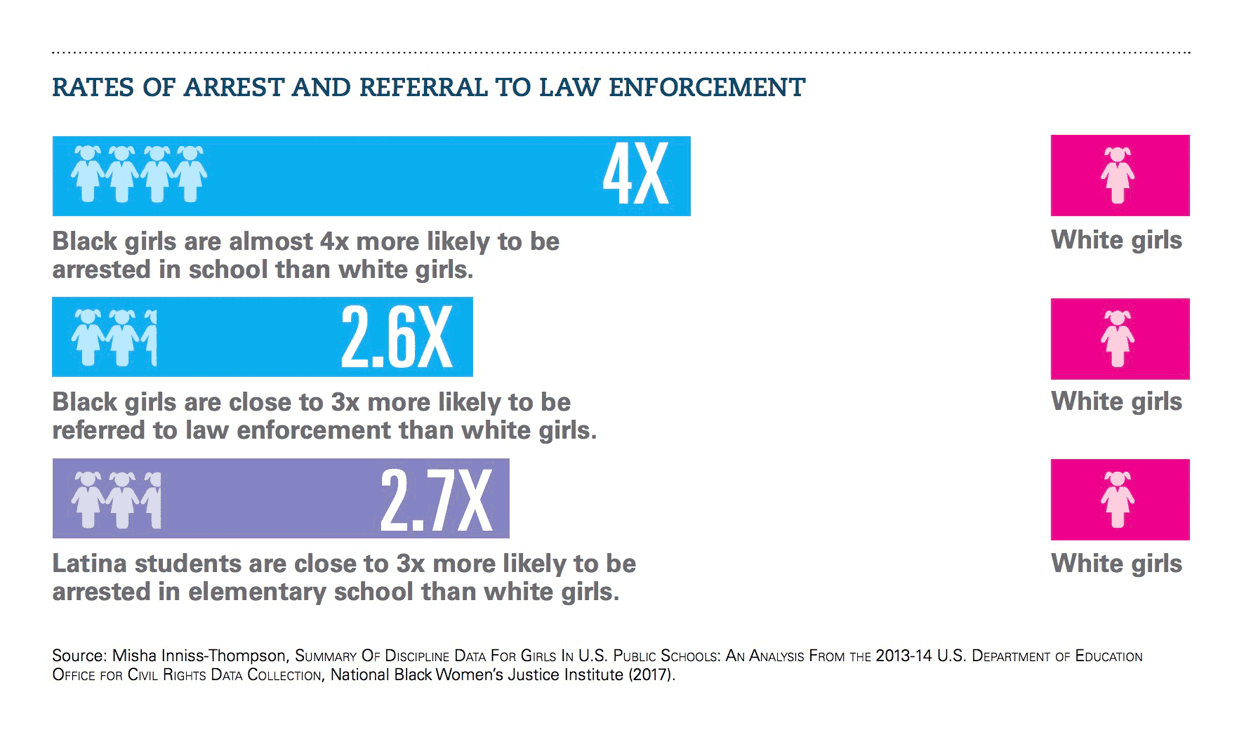

According to 2013-2014 data from the U.S. Department of Education, Black girls are 2.6 times as likely to be referred to law enforcement on school grounds as white girls, and black girls are almost 4 times as likely to get arrested at school. Disparities affecting Latinas are especially severe in elementary school where they are 2.7 times more likely to be arrested than young white girls.

In light of this data, schools and districts must work to improve interactions between girls of color and school resource officers (SROs), striving to keep girls of color safe and supported in schools and reduce disproportionate rates of contact in the justice system.

Schott Foundation is pleased to partner with the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality in the wide distribution of Be Her Resource: A Toolkit about School Resource Officers and Girls of Color, to districts, police departments, community, parent and student advocates across the country.

Schott Foundation is pleased to partner with the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality in the wide distribution of Be Her Resource: A Toolkit about School Resource Officers and Girls of Color, to districts, police departments, community, parent and student advocates across the country.

The toolkit, developed by National Black Women’s Justice Institute and Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, is centered on first-of-their-kind focus groups and interviews with SROs and girls to learn first-hand perspectives about their interactions. The research was focused on the South, an area often overlooked in related research. The report offers strategies and much-needed guidance based on the findings to improve relations between SROs and girls of color at schools.

The report finds that fewer than half of all states require SROs to receive youth-specific training, and, in particular, that SROs receive little, if any, training focused on girls of color, nor supports in the form of relevant community resources. Meanwhile, the line between criminal law and disciplinary codes have become blurred, given SROs’ wide discretion in carrying out their duties, and the lack of formal agreements between school departments and police departments that could clarify roles. The new report finds that only 19 states require such agreements.

Report key findings include:

- SROs described their most important function as ensuring safety and responding to criminal behavior, yet they report that educators routinely ask them to respond to disciplinary matters.

- SROs do not receive regular training or other supports specific to interactions with girls of color.

- SROs attempt to modify the behavior and appearance of girls of color to conform with mainstream cultural norms, urging them to act more “ladylike.”

- Girls of color primarily define the role of SROs as maintaining school safety — but they define their sense of safety as being built on communication and positive, respectful relationships with SROs.

African-American girls, in particular, identify racial bias as a factor in SROs’ decision-making process. African-American girls perceive that their racial identity negatively affects how SROs respond to them on campus.

Based on these findings, and with an eye to advancing action, the report presents guiding principles and policy recommendations that are designed to improve interactions between girls of color and SROs, with the ultimate goal of reducing these girls’ disproportionate rates of contact with the juvenile justice system.

Key recommendations for school districts and police departments include:

- Clearly delineate law enforcement roles and responsibilities in formal agreements.

- Collect and review data that can be disaggregated by race and gender.

- Implement non-punitive, trauma-informed responses to girls of color.

- Offer specialized training to officers and educators on race and gender issues and children’s mental health.

The report is part of a policy series conducted by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty aimed at reducing unfairly punitive treatment of girls of color. “Girlhood Interrupted,” released by the Center in June, found that adults view black girls as young as 5 years old as less innocent and less in need of protection than white peers, which may lead to harsher treatment by authorities.

The report’s detailed recommendations, which include providing officers with training to address adultification bias, are accompanied by hopeful examples of jurisdictions around the country that have taken steps to improve interactions between SROs and girls of color.