Blog

How the Eviction Crisis is also an Education Crisis

Of the myriad issues brought to prominence by the pandemic, schooling and housing have been two of the most prominent. While news outlets, pundits, and politicians will often treat them as separate concerns, where we live and where we learn are profoundly linked. To create a more racially just and equitable future for one, we must do so for both.

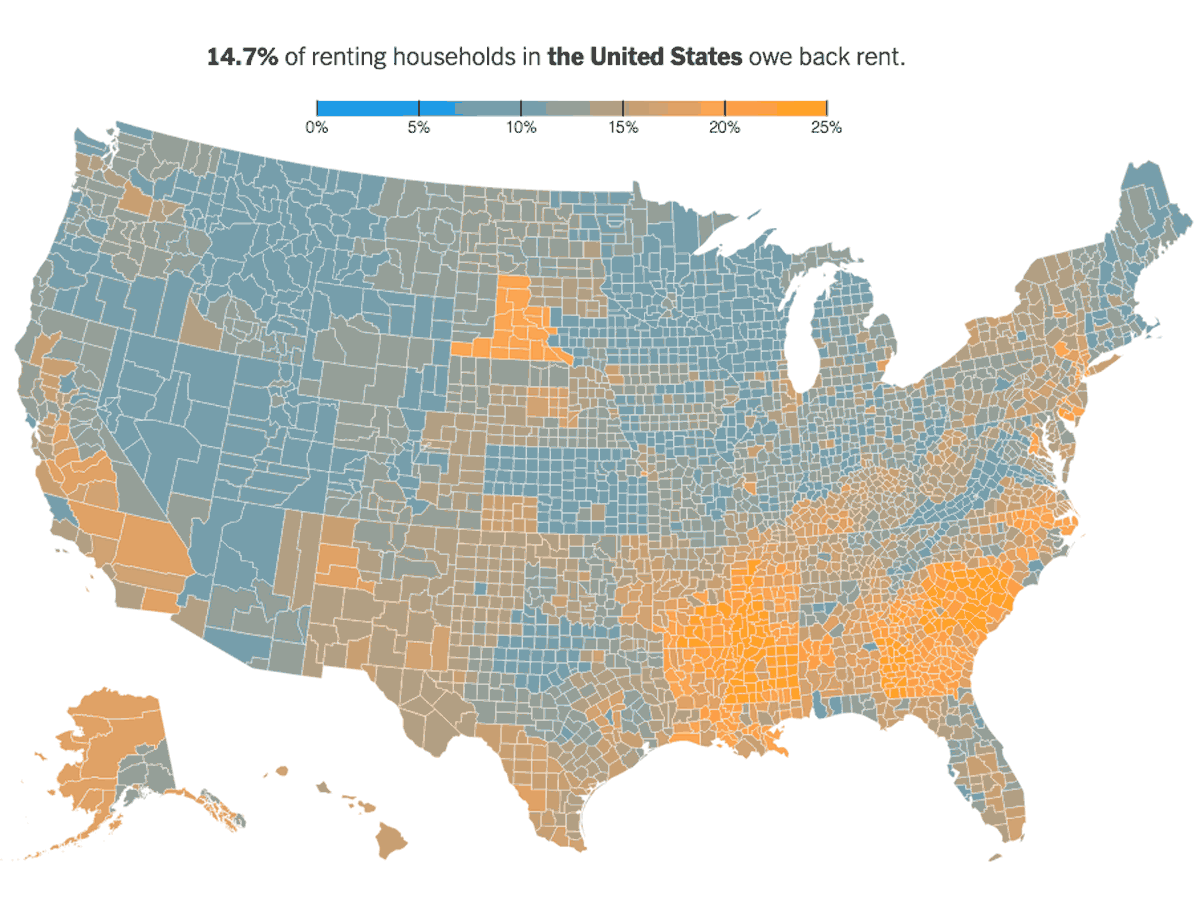

The CDC’s eviction moratorium ended July 31, thanks to a Supreme Court ruling followed by inaction from Congress and the White House. In a scramble earlier this week, the CDC issued an updated order that bans landlords from evicting tenants through October 31 in “counties experiencing substantial and high levels of community transmission levels,” which covers roughly 90% of the U.S. population. UPDATE: The Supreme Court struck down the CDC’s eviction moratorium on Thursday, August 27.

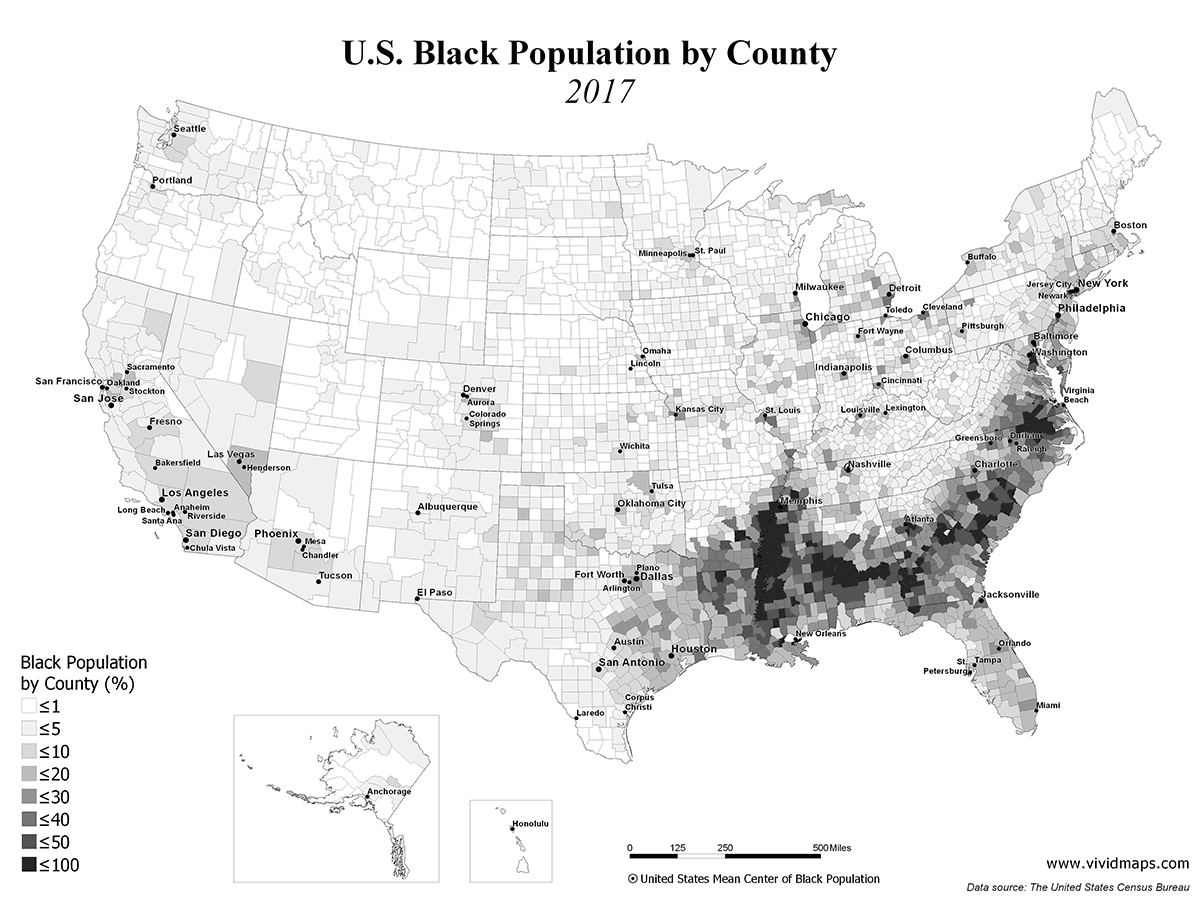

Unsurprisingly, the eviction threat specifically — and the decades-long housing crisis generally — has disproportionately impacted Black families. Compare these two maps: the first showing the percentage of Black residents by county and the second showing those counties with the most tenants who are behind on rent.

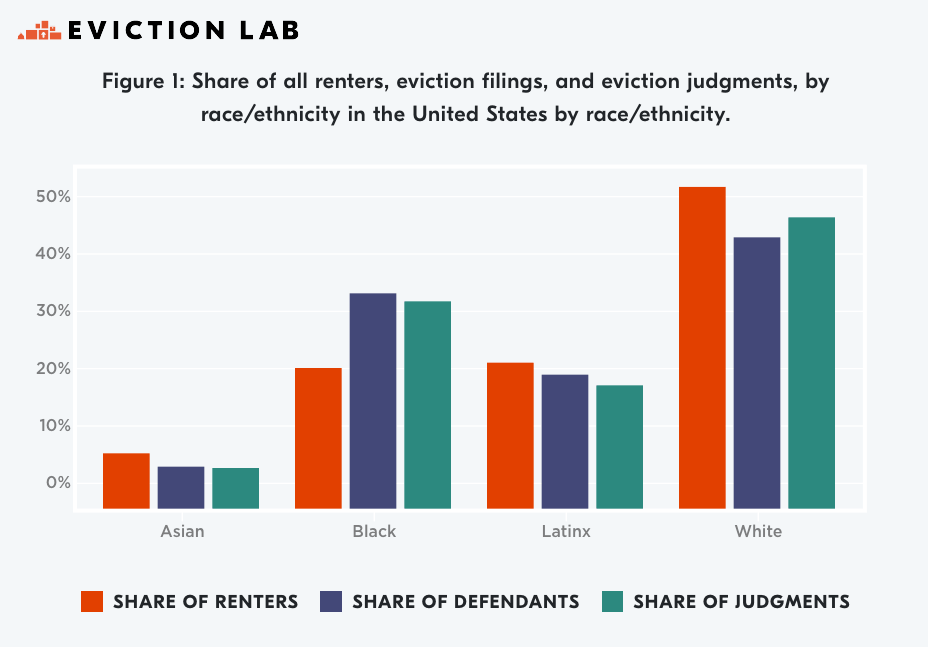

Recent nationwide data by Eviction Lab shows the Black eviction rate is disproportionately high.

Now that the eviction moratorium has been struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court, eviction proceedings will begin as the new school year begins, an added burden for children and families already uprooted.

But this is far from the first time that racial injustice in housing and education have intersected. Indeed, the two have been linked for over a century.

Segregation in Housing and Education Go Hand-in-Hand

As detailed most recently in Richard Rothstein’s groundbreaking book The Color Of Law, modern housing segregation, first imposed by the reactionary terror that ended Reconstruction, gained a veneer of legitimacy in the twentieth century. New Deal policies subsidized the development of whites-only suburbs with deeds that prohibited resale to African American families and provided white families federally-backed mortgages enabling homeownership.

At the same time, Black families could not apply for mortgages because of their race and instead had to utilize exploitive private markets to either rent at high costs or attempt to purchase over long periods of time, paying high-interest rates and not accumulating any equity until the full loan was paid off. Systems of zoning and redlining determined which neighborhoods whites and Blacks could live in, ensured that Black neighborhoods were undervalued and underinvested in, and allowed toxic sites to be built in Black neighborhoods.

After this pervasive set of policies and practices were ruled unconstitutional, there were no payments or programs to repair the damage done to Black families and increases in property value made integrating into White neighborhoods economically prohibitive. These economic barriers to integration created through housing policies persist today, and communities across the country are largely as segregated now as in the 1970s.

Segregation in public school districts has played a contributing role in this process, both shaping and being shaped by housing trends, redlining, underinvestment and white flight. While landmark desegregation rulings and laws did initially break down racial barriers within school districts, new, white districts in the suburbs were left untouched.

As school funding has always been largely based on property taxes, Black, Latinx, and low-income neighborhoods and cities were caught in a downward spiral. Stagnating home prices meant less funding for schools, which hurt the quality of the district, which negatively impacted home prices.

Unsurprisingly, since the 2008 crash and recession, homelessness has increased, disproportionately so for Black and Latinx families. Homelessness in California alone has increased almost 50% over the past decade.

In 2011, a Black mother in Akron, Ohio was jailed for sending her children to a better-funded school district in the city’s white suburbs, showing both the desperate lengths parents will go to provide a good education to their kids and the violent determination of the state to maintain these inequities.

Access to housing, whether owned or rented, isn’t just a matter of systemic or historical concern: it directly affects children’s education and life chances. Students experiencing homelessness are more likely to be suspended, more likely to be chronically absent, and less likely to graduate.

That’s why Schott has included Access to Affordable Housing as one of the twenty-five key indicators in our Loving Cities Index.

Interconnected Problems Require Interconnected Solutions

The policy solutions to inequitable school funding and inequitable housing have been known for decades.

For education, we must uncouple property taxes from district budgets and rely more heavily on progressive taxation, so that states can distribute funds where they’re needed most. For housing, the solution is rent control, good cause eviction standards, and an ambitious program of building new, quality public housing.

Though few states have made significant progress on these issues (New York being an inspiring outlier), the road to victory for both is the same: building parent, youth, and community organizations rooted in neighborhoods and linked across cities and states.

Many participants in housing struggles will find themselves working on education, and vice versa. That’s how groups like AQE could assemble a multigenerational, multiracial coalition to transform public school funding, but also call for rent, mortgage and eviction relief in their first set of COVID demands last year.

What is Philanthropy’s Role?

While it’s up to the people to grow organizations and movements, philanthropy can make a difference too, by providing strings-free funding and technical assistance for groups on the front lines of this important work.

In Schott’s #JusticeIsTheFoundation research released earlier this year, we found that only 0.8% of K-12 education foundations invested in racial justice work, which includes exactly the kind of grassroots organizing that’s so desperately needed today.

Parents, students, and educators are stepping up to make systemic change in this historic moment: it’s time for philanthropy to as well.

Photo by David Jackmanson.