Blog

Boston Stands Up for Public Schools and Democracy

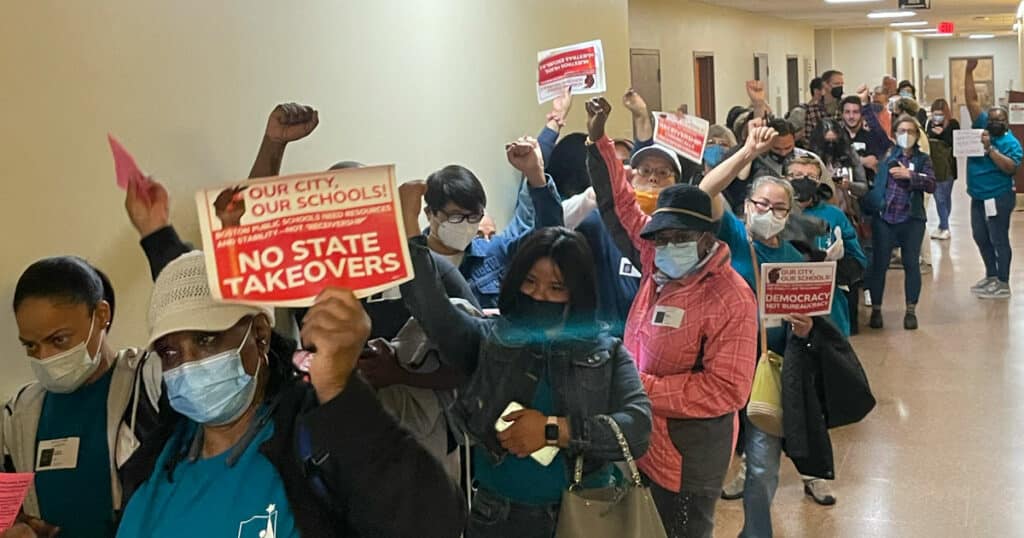

“Receivership is a coup! Nobody elected you!” was chanted by parents and advocates through face masks, ringing through the hallways outside this week’s state board of education meeting to determine the future of Massachusetts’ largest school district.

In the final months of Governor Charlie Baker’s administration, his appointed board overseeing the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), led by Education Commissioner Jeff Riley, is focusing on Boston Public Schools: aiming to execute a likely state takeover of the district by placing it in receivership.

Boston’s community isn’t standing for it.

A constellation of parents, students, and organizations showed up on Tuesday, including grassroots groups like the Boston Education Justice Alliance (BEJA), Massachusetts Education Justice Alliance (MEJA), Boston Student Advisory Council (BSAC), Families for COVID Safety (FamCOSa), and Citizens for Public Schools, as well as the American Federation of Teachers, Boston Teachers Union, NAACP, and Lawyers for Civil Rights.

State Takeovers Have a Checkered Track Record

State takeovers have a long track record, starting with schools in the city of Lawrence in 2012, and it’s a poor one. As the Bay State Banner reports:

In Massachusetts, state takeovers in Lawrence, Holyoke and Southbridge have not produced long-term gains in test scores or graduation rates. State interventions in two Boston schools — the Holland and Dever schools — have similarly failed to produce tangible progress. Additionally, the Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership — a consortium of schools the state removed from district control — has failed to produce tangible progress, with students scoring lower on standardized tests than their peers in district-run schools.

Not that standardized tests are a meaningful metric, but by the state’s own benchmarks, all districts currently under receivership have scores lower than Boston Public Schools. As the Boston Globe recently reported, “analysis of test scores, graduation rates, college enrollment, and a dozen other metrics in Lawrence, Holyoke, and Southbridge shows the state has failed to meet almost all its stated goals for the districts.”

Receivership means all decisions are made by a single state-appointed person, non-profit, or for-profit corporation, bypassing city and district officials, and voters. Up to 100% of teachers in a district under receivership can be replaced, popular school programs can be axed, and all with little transparency. Advocates say they don’t need a receiver to arrange school resources differently, what they need are more resources to address systemic problems that schools, parents, educators, and students are facing.

Taking Over Schools, Taking Over Democracy

The threat of a state takeover looms over what should be a democratic moment for the city: Boston Public Schools looks more likely than ever to transition to an elected school committee, finally moving away from an appointee model of governance. In a non-binding referendum last fall, 79% voted in favor of an elected school committee. An elected committee “is not a silver bullet,” said BEJA Director Ruby Reyes, “but it does mean more accountability.” A takeover would essentially sideline those elected officials — and their constituents.

Receivership would also complicate the ongoing search for a new BPS superintendent. MEJA Director Vatsady Sivongxay said, “if you put a district in receivership, you won’t get viable candidates.” MEJA, a Schott grantee partner, has been helping communities organize against receivership in communities across the state.

In addition, there is no established metric or criteria for a district in receivership to leave it and return to local control. The DESE board would have to vote to remove receivership, something it has never done.

The actions of DESE certainly give credence to the notion that the BPS takeover is a fait accompli, that their process at this point is window dressing for a pre-determined conclusion. DESE’s two year review of BPS took place almost entirely during the COVID-19 pandemic. Another review, a surprise two week audit of about a quarter of BPS schools in late March, took place, understood as the first step toward receivership. And just last week, DESE presented to Boston Mayor Michelle Wu a lengthy list of concerns about the district, giving her just three business days to respond. This week’s board meeting had a last-minute venue change, to a small meeting room with just a 25-person capacity, and the board limited all public comment to thirty minutes.

“This is our city, our school, our students, our community and our future. We know what the solutions are,” Sivongxay said. “Having a giant bureaucracy come into our public schools and dictate what we should do, while not giving resources and not being supportive or collaborative, isn’t good for our students.”

It’s also not lost on advocates that state takeovers are disproportionately imposed on racially diverse districts, and presently it’s three white men from the state — Governor Baker, Commissioner Riley, and Secretary of Education James Peyser — leading the charge to take over Boston’s school system, one of the most diverse districts in the country and led by three women of color — Mayor Wu, outgoing Superintendent Cassellius, and Boston School Committee Chair Jeri Robinson — as well as a majority-BIPOC school committee.

The Fight Back

Unlike some other districts, in which there was at least partial support by local officials, reaction to a possible takeover of BPS has been overwhelmingly negative. Mayor Wu came out against it, and the city council voted 12-1 last week in opposition.

As BEJA’s Reyes put it, “They weren’t expecting Boston to fight back.” BEJA, a Schott grantee partner, has been a key part of the growing community coalition to not only resist the state takeover, but build a stronger and more equitable BPS. They’ve been doing the painstaking work of expanding local awareness of the issues, holding public meetings, and building stronger relationships between parents. “Part of why there’s such strong resistance is we have been doing work with our members,” Reyes said. “We’ve been holding town halls where we invited Lawrence Public Schools elected school committee members to come and talk about the impact of their receivership.”

As is often the case with grassroots organizing, the most important work is done outside of the public eye. “I don’t think people understand how much work it is to prepare people to have meetings, to do strategy work — that’s the part a lot of people don’t see,” Reyes said. “They see the rally and the action, but they don’t see us working with that mom to encourage her to even consider giving testimony at a hearing, encouraging her throughout the process, ‘you can do this!’ That’s a really beautiful part of our organizing work.”

Next Steps

The board’s next meeting is June 28, at which point it’s likely any receivership proposal will be voted on. The Boston community will be ready, and in the meantime there are actions you can take:

Send a message to the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education >