Exclusive new data: When it comes to racial justice, education philanthropy still doesn't walk the talk

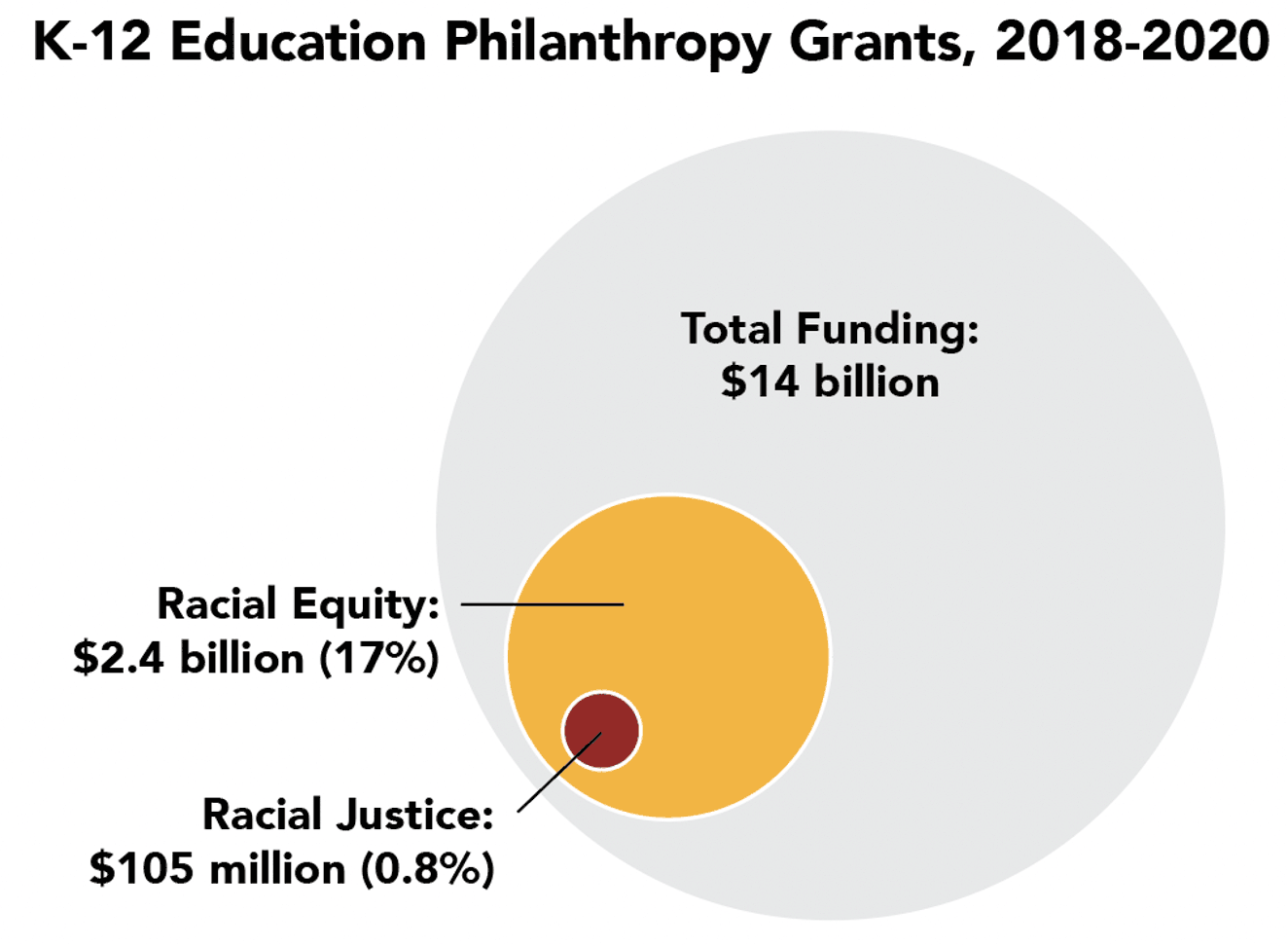

Education is the second most-funded issue area in philanthropy. But how much of that is allocated to racial equity and racial justice work?

The Schott Foundation for Public Education has worked with Candid for the past two years to critically examine the ultimate measure of K-12 education philanthropy’s priorities: where the grant dollars go. With our #JusticeIsTheFoundation project we can assess the collective philanthropic impact of giving in the education sector through a lens of racial equity and racial justice, telling the story of what we prioritize and revealing blind spots in our collective response.

The full report is due to be released soon, but as a Philos reader, you’re getting early access to our topline data findings based on reported grantmaking from 2018-2020. (Note that 2020 grantmaking data is not yet 100% complete in Candid’s database, due in part to the disruption of the pandemic, but enough has been submitted to justify inclusion.)

How do we define “racial equity” and “racial justice?”

We took care to parse out grants that may look similar on the face, but actually have significant differences.

Racial equity refers to grants designed to close the achievement gap that persists between racial groups. Grants for racial equity include support for programs such as racial bias trainings for teachers or mentorship programs for Black and brown students.

Racial justice refers to grants designed to close the opportunity gap — the underlying systemic injustices that create the achievement gap in the first place. Racial justice grants focus explicitly on empowering people closest to the problem (families and students) organizing in their communities to change the systems and structures that generate and reinforce racial inequity. Racial justice grantmaking supports building community power, supporting policy change, engaging with policymakers, building partnerships with advocates to advance racial equity.

In short, racial equity grants address symptoms, while racial justice grants address root causes by strengthening the foundation, or bedrock, of efforts to achieve equity. For the purposes of this project, racial justice grants are considered a subset of racial equity grants.

Top 5 takeaways from the latest data:

- At less than 1% of K-12 education grantmaking, philanthropy still drastically underfunds racial justice work.

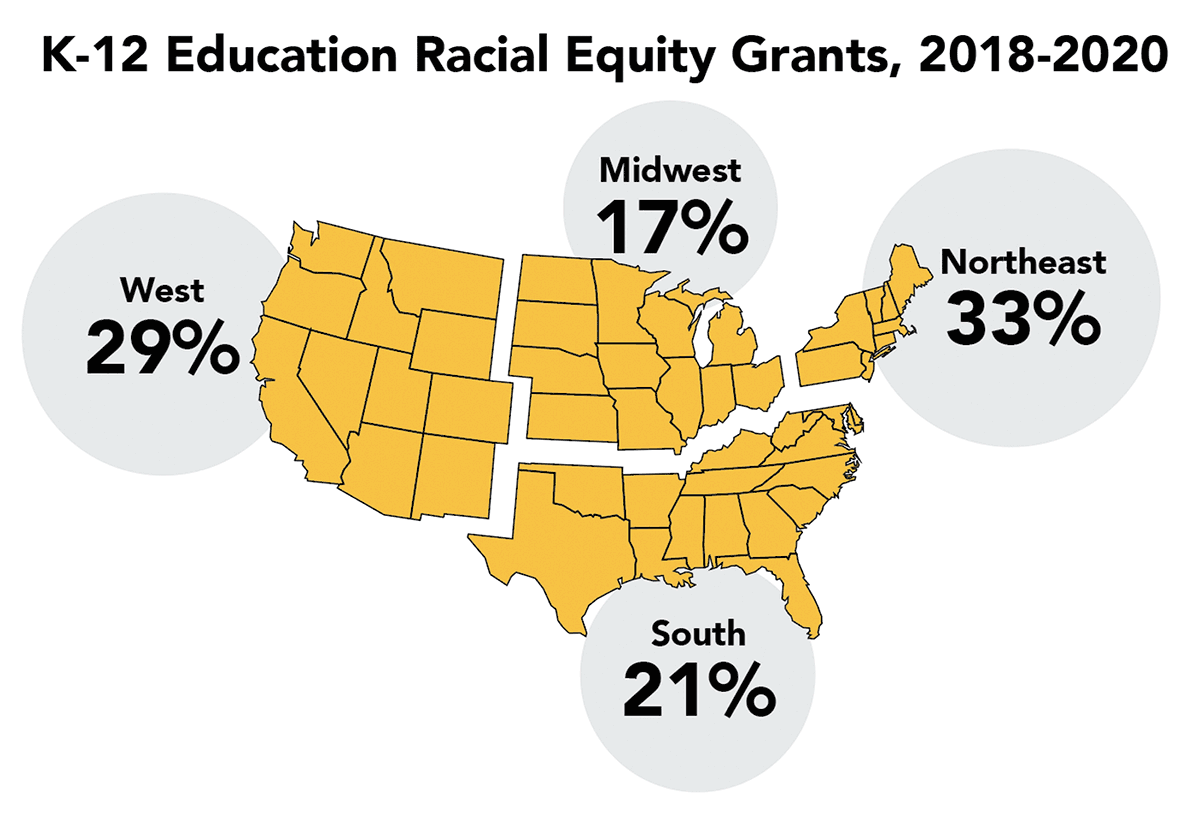

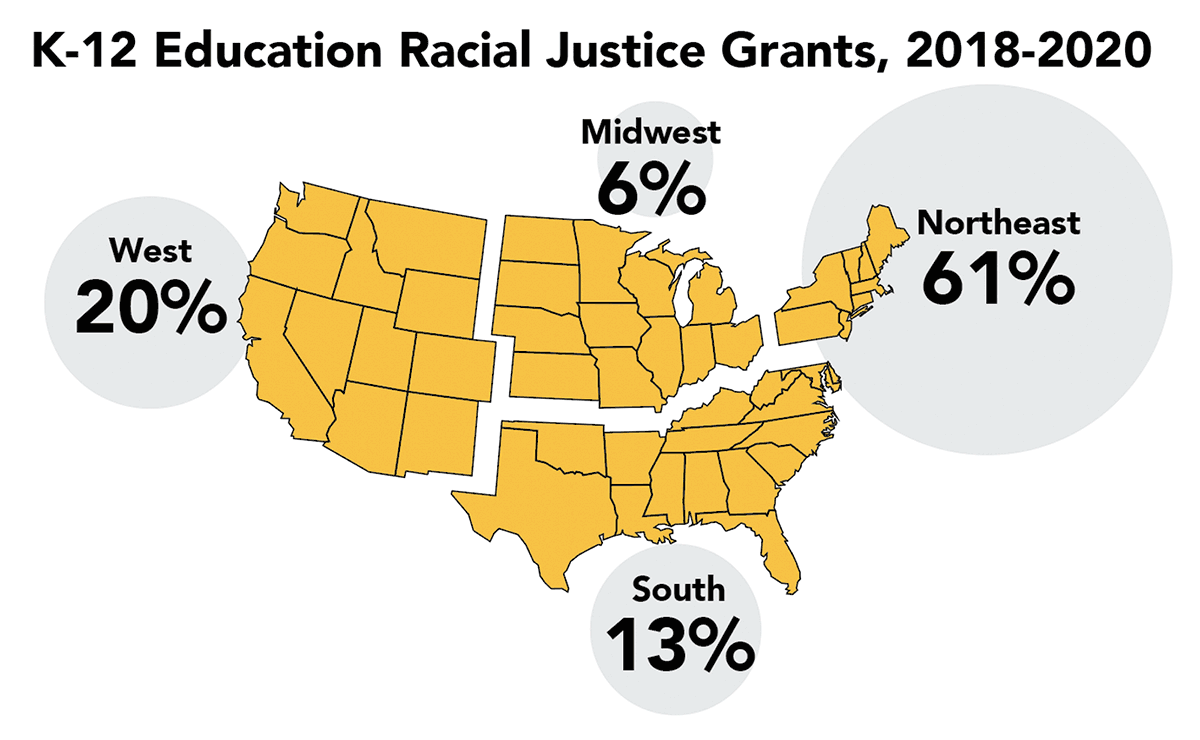

- The geographic distribution of racial justice grants is disproportionately concentrated in the Northeast.

- Racial equity dollars did not noticeably increase in 2020, despite stated commitments by funders, Foundation 1000 (F1000) data suggests.

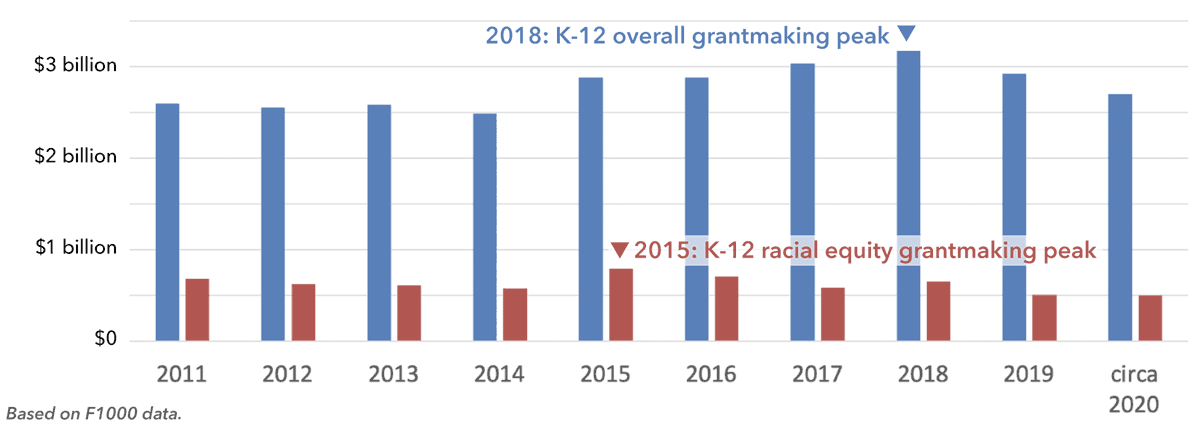

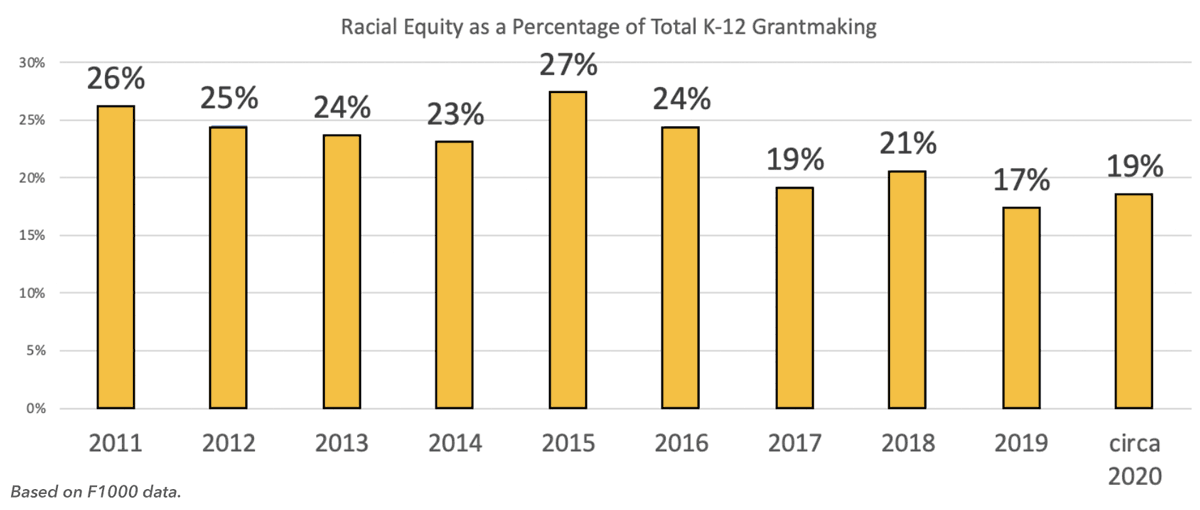

- Racial equity grantmaking has actually declined since 2015, when funding spiked after the Ferguson and Baltimore uprisings, F1000 data suggests.

- K-12 grantmaking peaked in 2018 and has declined ever since, F1000 data suggests.

Racial Equity & Justice Grantmaking By Geography

Racial justice grant dollars are disproportionately targeted to grantees in the northeast, while racial equity overall is more evenly balanced geographically.

Changes Over Time – Based on F1000 Data

Candid’s Foundation 1000 (F1000) data is limited to grants of $10,000 or more awarded by a set of 1,000 of the largest U.S. private and community foundations each year. Because it is somewhat limited as a dataset, the absolute dollar amounts don’t matter as much as the change over time. It’s a sample that lets us detect trends in the sector.

K-12 total grantmaking peaked in 2018, while racial equity grantmaking peaked in 2015:

Below is the percentage of racial equity grant dollars as a percentage of total K-12 total grant dollars. Both the total dollars and percentage have been trending downward since 2015. The slight percentage uptick in 2020 is solely due to a shrinking of the total K-12 grant dollar amount: it’s a larger slice of a smaller pie. Note that dollars in this calculation are not adjusted for inflation.

What’s next

The data is clear: all of us in education philanthropy must step up to make the bold investments that the movements and this moment demand of us. This will take visionary thinking, difficult conversations, and new commitments to transparency and participatory grantmaking — but you’re not alone. Also in this issue, read and listen to an interview with Dr. Alandra Washington, who has spent her career advancing racial equity in philanthropy, and explore the growing interest in funders endowing their grantee partners as a way to dramatically shift wealth and power.